What is Process Evaluation?

Process Evaluation (PE) is defined as a systematic analysis of the operation of a graduation program to identify how its processes and activities lead to achieving the results defined in its design. This evaluation also detects bottlenecks and good practices in implementing these processes and activities to offer recommendations and areas for improvement (Mendoza, Moreno-Sánchez, and Maldonado, 2015). Conducted parallel to program execution, PE focuses on processes directly influencing the program’s objectives or goals.

Given the subject of analysis, it mainly employs qualitative data from structured interviews with program implementers and participants. Quantitative data, such as structured surveys estimating numerical indicators, may also be used. These indicators measure effectiveness (assessing whether processes contribute to objectives) or quality (identifying perceptions of implementers’ performance and beneficiary satisfaction).

How is Process Evaluation done?

1. Hypothesis Construction

Guides the evaluation exercise. The hypothesis must be clear and direct the objectives’ formulation.

2. Setting Objectives

3. Defining Scope

4. Development

Central to the evaluation and conducted alongside program implementation.

Key moments in implementation:

- Program start: Collect baseline/context data.

- Program end: Gather data to compare expected and achieved outcomes.

- Intermediate stages: Evaluate key product distribution for goal achievement.

4.1 Detailed Program Description

4.1. Detailed Program Description: Analyze operation and function via four aspects:

Analyze operation and function via four aspects:

- Factual/contextual analysis

- Value chain construction.

- Actor mapping and responsibility identification.

- Detailed program timeline.

4.2. Effectiveness Analysis

Determines goal achievement through:

- Indicator definition.

- Indicator estimation.

- Indicator analysis.

Formulate indicators for each substantive sub-process, integrating qualitative and quantitative insights.

4.3. Quality Analysis

Evaluates implementer performance and participant feedback.

Quality indicators measure utility, timeliness, sufficiency, and satisfaction from both implementers’ and participants’ perspectives.

Conducted via:

- Indicator definition.

- Indicator estimation.

- Indicator analysis.

Contextualize results and triangulate data from other steps.

4.4. External Factors Analysis

Identifies uncontrollable external factors affecting processes and outcomes. This analysis strengthens recommendations using the value chain for each sub-process.

4.5. Identifying Best Practices and Bottlenecks

Identifies, describes, and analyzes these elements, focusing on their causes and consequences.

Recommendations aim to refine program design using the value chain for each sub-process.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Provide an overall evaluation and propose strategic planning guidelines for short- and medium-term corrective actions.

What is Effects Evaluation?

Effects Evaluation (EE) within the Platform framework assesses whether and to what degree an intervention achieved effective changes in beneficiaries’ behavior and characteristics (CEDE, 2015). EE collects information and evidence about actual program results on participants, encompassing various methodologies including qualitative and quantitative strategies. Different methodologies vary in required information level, result representativeness, and confidence in attribution levels.

Results Evaluation (RE) and Randomized Control Trial (RCT) Impact Evaluation are two EE methodologies implemented by the Platform for Graduation cases. They differ in their ability to define attribution levels (i.e., causality). RE collects information before and after intervention from program participants to quantify population changes and relate them to program implementation. Impact Evaluations use program design characteristics or statistical tools to gather information from both participants and a control group, allowing isolation of the program’s real causal effect.

The Platform promotes mixed methodologies, combining quantitative and qualitative information to better understand quantitative results and inform policy discussions. Qualitative strategies include interviews, focus groups, and autobiographical accounts (Life Stories).

What is the Effects Evaluation for?

EE helps justify program existence, continuity, or scaling. It helps designers and implementers demonstrate program utility and objective achievement. This information enables design changes when needed and testing new procedures. Results information is crucial for assessing project economic sustainability through cost-benefit evaluations.

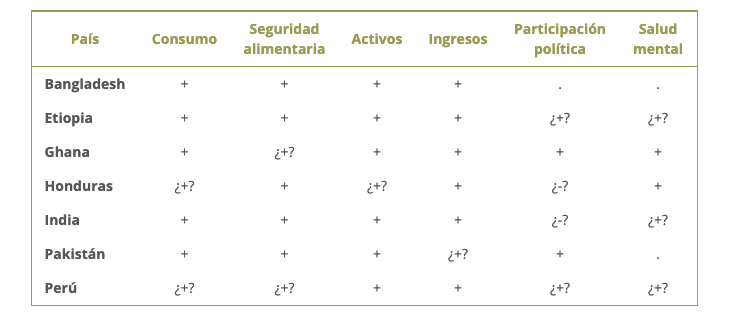

Graduation Programs demonstrate positive results of accompanying and supporting innovative designs with rigorous evaluations. BRAC, Ford Foundation, and CGAP have implemented RCT Impact Evaluations, proving Graduation Programs’ benefits.

¿+? and ¿-? refer to positive and negative effects respectively, but without finding statistical evidence to support it.

Source: Banerjee et al. (2015); Bandiera et al. (2011); Briefs IPA.

How is the Effects Assessment done?

The Results Evaluation contemplates the collection of quantitative data before and after implementation, in order to compare the status of participating households with and without the program. The minimum requirements in the methodological design of an RE include:

1. Identification and prioritization of the results to be evaluated

Prior to the planning and design stage of the Outcome Evaluation, the identification and prioritization of the results to be measured allows to clearly establish the objectives and scope of the evaluations that are proposed. All programs with a Graduation approach have a series of common objectives, so that particular results are expected for all cases.

2. Construction of the indicators of interest

Each result to be evaluated, chosen during the previous stage, must have at least one clear and quantifiable indicator from which it can be determined whether or not progress has been made in those particular results. The indicators should be chosen based on the CREMA methodology presented by DNP (2012) and developed by the World Bank, in which the indicators should be:

- Clear, i.e. they should be precise and unambiguous,

- Relevant, in that they are appropriate for the particular outcome of interest,

- Economical, i.e. their calculation costs are reasonable,

- Measurable, i.e. amenable to external validation, and

- Adequate, in that they provide sufficient information to estimate performance.

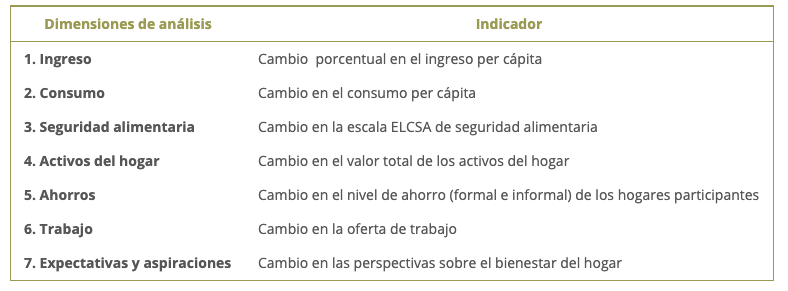

For the case of the Platform, the following Indicators have been defined:

3. Setting targets in terms of indicators

A process suggested by McNamara (2006) is to establish, in light of the defined objectives and results, the targets for the proposed indicators. This is an exercise that should be proposed in conjunction with the program’s implementing institutions, based on their expectations of the program.

4. Design of data collection tools

The main objective of this requirement is to establish the information required for the construction, estimation and interpretation of the indicators defined in the previous stages. For the evaluation of results, a complementary approach between qualitative and quantitative research techniques will be used. This approach will be used to provide feedback between the findings of these two techniques in order to understand more clearly the results of the evaluation and the effects on the participants, as well as the channels through which these are made effective.

Thus, the adaptation of this methodology to each particular case involves clearly specifying the activities to be carried out within the quantitative analysis and the qualitative analysis, and the way in which these two analyses are expected to interact. The quantitative analysis includes the elaboration of a survey to be carried out before and after the implementation, whose sample design is defined based on the availability of resources, the change to be statistically detected in the group mean before and after the intervention, as well as the size of the intervention. Qualitative analysis may include, among others, focus groups, group or individual interviews, and life histories. The choice of tools depends on the complement sought between the two types of analysis.

5. Information and results analysis strategy

The proposed RE strategy allows for two types of analysis of the information collected. The first corresponds to the analysis of the indicators, based on the comparison between the baseline and the final line. On the other hand, the second type of analysis seeks to look at structural changes in the results from different sociodemographic variables.

Impact Evaluation by RCT

The Results Evaluation contemplates the collection of quantitative data before and after implementation, in order to compare the status of participating households with and without the program. The minimum requirements in the methodological design of an RE include:

1. Identification and prioritization of the results to be evaluated

Prior to the planning and design stages of the impact evaluation, the identification and prioritization of the results to be measured allow establishing clear objectives and determining the scope of the proposed evaluation. For example, within the framework of the Platform, all Graduation Programs have certain common achievements and therefore particular effects are expected, such as poverty reduction, increased household food security, creation of sources of self-employment, increased levels of savings, creation of social and life skills, and personal growth (De Montesquiou et al, 2014. Banerjee et al, 2015.). Still, the process of contextualizing Graduation Programs may require other variables. Clarifying which outcomes are of interest and useful to implementers and evaluators is necessary before moving forward with evaluation design.

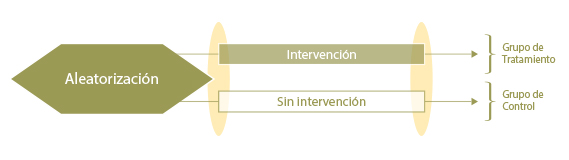

2. Randomization strategy

The challenge of an RCT is to have a control group that is on average as similar as possible to the treatment group, and one of the ways to achieve this is through randomization. Therefore, randomization is a fundamental part of an RCT. The literature suggests different types of strategies that allow an efficient design to be obtained, depending on the particular context, without sacrificing the robustness of this type of evaluation. There are at least three elements of a program that can be randomized: access, temporality and invitation to participate, both at the individual and group level (Glennerster and Takavarasha, 2013). As suggested by Glennerster and Takavarasha (2013) and Bernal and Peña (2011), the selection of a randomization strategy will depend on the particular context and constraints of the proposed evaluation. Each of the strategies will have practical, policy, methodological, and ethical implications.

3. Power calculations and sample design

The power of an RCT design corresponds to its ability to identify the perceived effects as statistically significant (at a given α confidence level). That is, it is the ability to identify that the increase or decrease in one of the outcome variables, when comparing information from treated and controls, is not by chance, but that these results would be present in the generality of cases in which the evaluated program is implemented.

Power depends critically on (1) the randomization strategy, (2) the number of treated households, (3) the number of households surveyed, (4) the level of statistical confidence desired for the results, and (5) the periodicity of the surveys. Because of this, power analyses also determine the sample design with which quantitative information would be collected.

4. Design of data collection tools

It is suggested that RCTs complement their quantitative techniques (survey) with qualitative research strategies. This approach allows the results of each technique to feed back into each other in order to have more complete and policy-relevant results. This also allows for greater clarity in the understanding of the evaluation and the effects on participants, as well as the channels through which these are made effective.

5. Monitoring strategy

Impact evaluations by RCTs require the design and development of follow-up and randomization protocols. Part of the validity of the results of this type of exercise depends on the households/participants defined as treated actually receiving the program, while households/participants who were assigned to controls do not. In the same way, continuous follow-up should be maintained for existing interventions other than the one evaluated.

References

Centro de Estudios sobre Desarrollo Económico – CEDE (2015). Metodología para la Evaluación de Resultados. Documento Interno de Trabajo. Plataforma de Evaluación y Aprendizaje de los Programas de Graduación en América Latina. CEDE – Facultad de Economía, Universidad de los Andes.

Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, N. Goldberg, D. Karlan, R. Osei, W.Pariente, J. Shapiro, B. Thuysbaert, and C. Udry (2015). “A Multifaceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries.” Science 348, no. 6236 (May 14, 2015).

Bandiera O., Burguess R., Das N., Gulesci S., Rasul I. Shams R. y Sulaiman M. (2011). “Asset Transfer Programme for the Ultra Poor: A Randomized Control Trial Evaluation”. CFPR Working Paper 22. Disponible en: https://www.microfinancegateway.org/sites/default/files/publication_files/asset_transfer_programme_for_the_ultra_poor-_a_randomized_control_trial_evaluation.pdf

Departamento Nacional de Planeación – DNP (2012). Guias Metodológicas Sinergia – Guía para la Evaluación de Políticas Públicas. Bogotá D.C., Colombia.

McNamara, Carter (2006). Basic Guide to Program Evaluation. Disponible en: managementhelp.org/evaluation/program-evaluation-guide.htm

De Montesquiou, A., Sheldon, T., De Giovanni, F,. and Hashemi, S. (2014). From Extreme Poverty to Sustainable Livelihoods: A Technical Guide to the Graduation Approach. Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) and BRAC Development Institute.

Glennerster, R., & Takavarasha, K. (2013). Running randomized evaluations: A practical guide. Princeton University Press.

Bernal, R., y Peña, X. (2011). Guía práctica para la evaluación de impacto. Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Economía, Centro de Estudios sobre Desarrollo Económico.

What are Life Histories?

The Life History (LH) is a qualitative research technique, which is part of the biographical method (Sanz, 2005), with which an informant’s account of his own life is constructed, together with the collection and analysis of additional information from the context, coming, for example, from documentary records and interviews with people from the social environment of the interviewee. For the case of interest, the informant is the selected participant of the program to be evaluated.

The purpose of incorporating life histories in the Platform is to understand the current attitudes and behaviors of the program participants under evaluation, and how attitudes and behaviors are influenced by the intervention.

The HVs are of an individual nature, so it is mainly based on private interviews with the participants who decide to participate in this exercise. The Platform’s interest is to develop multiple autobiographical accounts, thus collecting the accounts of several participants in the program in a defined period of time. The number of HVs is defined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the variability of the target population with the program to be evaluated. In the same way, the individual interviews of the households under follow-up are complemented with interviews with program officials or other households, in order to complement the participant’s perspective.

What are Life Stories useful for?

The qualitative information gathered from life histories is very useful for program designers and implementers because, on the one hand, it offers signals about the perception that participants have about the processes and activities of the evaluated program and, on the other hand, it allows identifying the changes that the program has produced in households, as well as understanding the mechanisms or channels through which these changes have been generated. It is a particularly useful tool when seeking to understand the effects of the program on variables that are complex to measure, such as those related to well-being, empowerment, aspirations and expectations, use of time, among others.

In this way, life histories are a fundamental complement to impact evaluations, because they allow understanding the quantitative results of these evaluations and facilitate the understanding of changes in complex variables; This has been demonstrated by the use of this methodology in previous evaluations of graduation programs in Ethiopia – Ethiopia Graduation Pilot- (Sengupta, 2012), Pakistan – Pakistan Graduation Pilot- (Kabeer, Huda, Kaur and Lamhauge, 2011) and India -Trickle Up Ultra Poor Program- (Huda and Kaur, 2011; Sengupta, 2012; Kabeer, Huda, Kaur and Lamhauge, 2011).

How are the Life Histories done?

The methodological design of the Life Histories contemplates 3 main elements. These are:

Definition of the target population

The target population of the Life Stories corresponds to participants of the program to be evaluated. As in other qualitative methodologies, Life Stories seek to delve into the analysis of a few individuals in order to gain depth in their analysis; for this reason, it is important to define certain selection criteria, thus providing the greatest variability in the subjects of study.

Although the selection criteria depend on each case, some possible considerations are:

- Geographic representation.

- Different household compositions.

- Different level of market isolation of relevance.

- Different conditions of access to the program evaluated (e.g. vulnerability due to poverty or victims of conflict, among others).

Definition of collection periods

The construction of the Truncated Life Histories is carried out from periodic visits to participating households throughout the implementation of the program. The dates of the visits will be adjusted with the development of the Graduation Program at key moments of its implementation.

With the purpose of generating an environment conducive to the interview and seeking the comfort and tranquility of the interviewee, the visits will be carried out at the times, places and situations preferred by the interviewee.

Information Collection

Primary Information

Primary information comes mainly from interviews with participants. It is important to clarify that the participation of households in this exercise must be entirely voluntary, and that this approval must be supported by written consent from the participating households.

Each of the interviews should have a clear objective, which should guide each of the visits. It is suggested that a first visit be developed for exploratory purposes and that the rest of the visits be developed depending on (1) the particular information requirements of each evaluation and (2) the development of the program.

The Platform encourages that the follow-up of the selected households (the “focal households”) be developed in conjunction with additional interviews to other households in the same community (“satellite households”), and therefore receive the program in a similar way. Likewise, it is pertinent to conduct interviews with officials close to the households during implementation. In the case of the Graduation Programs, this could be equivalent to households assigned to the same manager. These additional interviews allow triangulating information to better understand the changes generated -or not- in the households participating in the Life Stories, as well as their context or ‘window’ of opportunities (Moreno-Sánchez et al., 2017).

Secondary information

Before -and during- the exploratory visits, a bibliographic review of secondary information for the municipalities/localities where the life histories will be carried out is sought. The main sources of information include the entity in charge of producing national statistics, libraries, municipal technical assistance entities, the municipal mayor’s office, the governor’s office (land-use plans, municipal development plans, agricultural diagnoses, etc.). The objective of collecting secondary information is to know and understand the general context of the municipalities/localities where the life histories will be applied, a context that can differentially affect households’ experiences with the program.

References

Huda, K and Kaur, S. 2011. ‘‘It was as if we were drowning’’: shocks, stresses and safety nets in India, Gender & Development, 19:2, 213-227

Kabeer, N., Huda, K., Kaur, S., and Lamhauge, N. 2011. “And Who Listens to the Poor?” Shocks, stresses and safety nets in India and Pakistan. BRAC Development Institute. Disponible en: http://www.merit.unu.edu/events/event-abstract/?id=986

Lybbert, T. and Wydick, B. (2016). “Poverty, Aspirations, and the Economics of Hope”. Economic Development and Cultural Change.

Ray, D. (2002). Aspirations, Poverty and Economic Change. New York University and Instituto de Análisis Económico (CSIC). URL: https://www.nyu.edu/econ/user/debraj/Courses/Readings/povasp01.pdf.

Sanz, A. 2005. El método biográfico en investigación social: Potencialidades y limitaciones de las fuentes orales y los documentos personales. Asclepio. Vol. 57, No 1. Disponible en: http://www.eduneg.net/generaciondeteoria/files/SANZ-2005-El-metodo-biografico-en-la-invest-social.pdf

Sengupta, A. 2012 (a). Pathways out of the Productive Safety Net Programme: Lessons from Graduation Pilot in Ethiopia. Working Paper. The Master Card Fundation and BRAC Development Institute. Disponible: http://www.microfinancegateway.org/sites/default/files/publication_files/pathway-out-of-psnp.pdf

Sengupta, A. 2012. Trickle up – Ultra Poor Programme. Qualitative Assessment of Sustainability of Programme Outcomes. The Master Card Fundation and BRAC Development Institute. Disponible en: http://www.microfinancegateway.org/sites/default/files/publication_files/trickle-up-up-program-final-qualitative-assessment.pdf

Moreno-Sánchez, R., Rodriguez C.A., Martinez, V., y Maldonado J. 2017. Historias de Vida-PxMF. Reporte Final. Parte I: Introducción. Documento Interno de Trabajo. Plataforma de Evaluación y Aprendizaje de los Programas de Graduación en América Latina. CEDE-Facultad de Economía, Universidad de los Andes.

With the support of: